Rickettsia Bacteria

Definition, Examples, Characteristics, Disease

Definition

Rickettsiae (Rickettsia bacteria) is a genus that consists of small, obligate intracellular parasites of human beings, animals, and plants. As such, they can only multiply/proliferate within a host as endoparasites.

While they negatively affect different types of hosts, some of these bacteria have been shown to form a symbiotic relationship with some invertebrates. Unlike most bacteria, members of the genus Rickettsia need a vector for host transmission.

Some of the most common vectors for Rickettsia bacteria include:

- Mites

- Flea

- Lice

- Ticks

- Leafhoppers

* Rickettsia-like bacteria include Anaplasma, Ehrlichia, and Coxiella burnetii. Like Rickettsiae, Anaplasma and Ehrlichia are intracellular pathogens that require vectors for transmission.

While Coxiella burnetii does not need a vector for transmission, it can be transmitted through air, water, or contaminated food. It's also an intracellular bacterium that shares some morphological traits with Rickettsia.

Examples

In general, the genus Rickettsia has been divided into three main groups depending on the type of infection/disease they cause.

These include:

The typhus group (TG) - This group includes Rickettsia bacteria which is transmitted by fleas and lice. They include Rickettsia prowazekii and Rickettsia mooseri (also known as Rickettsia typhi). These bacteria are responsible for Brill-Zinsser disease and murine typhus respectively.

Spotted fever group (SFG) - Members of this group include Rickettsia rickettsii and Rickettsia conorii. They are transmitted by ticks (or infected mites in some cases) and are responsible for rocky mountain spotted fever and boutonneuse fever respectively.

Some of the other species in this group include:

- Rickettsia slovaca

- Rickettsia akari

- Rickettsia sibirica

- Rickettsia africae

- Rickettsia massiliae

Scrub typhus group - This group consists of the species Rickettsia tsutsugamushi which is naturally transmitted by the chigger mite. Today, however, this species has been renamed Orientia tsutsugamushi and re-classified under the genus Orientia in the family Rickettsiaceae.

Characteristics

Morphology and Structure

Rickettsiae are some of the smallest bacteria, ranging from 0.3 to 0.5 um in diameter and 0.8 to 2.0 um in length. They are significantly smaller compared to eukaryotic cells which range from 10 to 100um in diameter.

The variation in the size of these Rickettsia may be due to the type of species or general shape of the bacteria. While some are coccoid/spherical in shape (e.g., Rickettsia rickettsii which may also have a coccibacillus morphology), others like Rickettsia typhi are rod-shaped.

Many species in this genus are pleomorphic and therefore capable of changing their shape depending on environmental conditions.

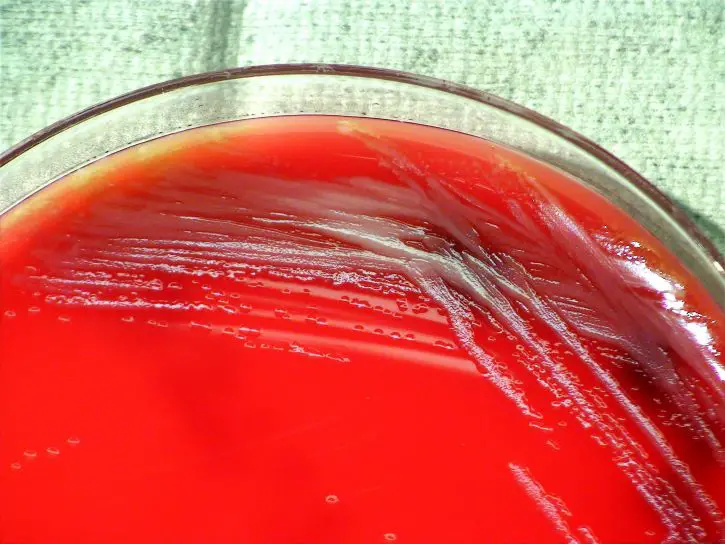

When viewed under the microscope, they may occur singly or in pairs. As well, they may form strands that are responsible for the visible plaques (rickettsiae plaques) observed in infected chick embryo - Plaque formed by R. rickettsii may range from 2 to 3 mm in diameter.

With regards to structure, Rickettsia bacteria is Gram-negative and thus has a thin peptidoglycan layer in their cell wall. Typical of Gram-negative bacteria, their cell envelope consists of three main layers including the inner cell membrane, a thin cell wall surrounding the inner membrane as well as the outermost membrane which surrounds the cell wall.

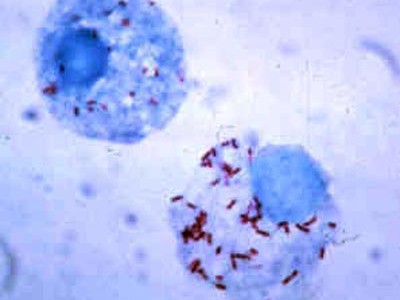

Although Rickettsia is described as Gram-negative bacteria, results may vary when they are stained using Gram stain. For this reason, other stains like Giemsa are often used to identify them.

They are also characterized by a small genome which has been attributed to reductive evolution.

See info on Gram positive and Gram negative bacteria.

Some of the other structural characteristics of Rickettsia bacteria include:

· Their cell wall contains diaminopimelic acid

· As Gram-negative bacteria, they lack teichoic acid

· Intracytoplasmic invaginations of the plasma membrane may be observed when viewed under a powerful microscope

· They have lipopolysaccharide (LPS) which consist of lipid and polysaccharide

· SFG rickettsia are characterized by MOmpA proteins in their outer membrane while OmpB proteins can be found in the outer membrane of all Rickettsia

· Non-motile

Ecology and Distribution of Rickettsia Bacteria

As obligate intracellular pathogens, Rickettsia bacteria cannot survive outside the body of a host. For this reason, they cannot be found living freely in terrestrial or aquatic environments. However, they can be found in different types of vectors (arthropods) including mites, lice, fleas, and ticks.

By focusing on infections/diseases caused by these bacteria, studies have shown that Rickettsia are well distributed worldwide (except in Antarctica). However, certain species can be found in abundance in specific regions depending on the type of host present, climatic conditions, as well as the type of vector.

As well, species like Rickettsia felis and Rickettsia typhi can be found in different parts of the globe where they are well distributed.

· USA: In the United States, R. rickettsii is the main cause of Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever

· Northern Australia: R. australis and R. honei are some of the most common Rickettsia in Northern Australia where they are responsible for Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever

· In parts of Asia, Africa, and Europe, R. conorii is the prevalent Rickettsia species responsible for Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever

· Asia: In Asia, R. typhi is the primary cause of typhus group infections

* Today, human activities and climate changes among other changes have a direct influence on vector behavior which is, in turn, influencing the distribution of Rickettsia bacteria.

Reproduction/Proliferation

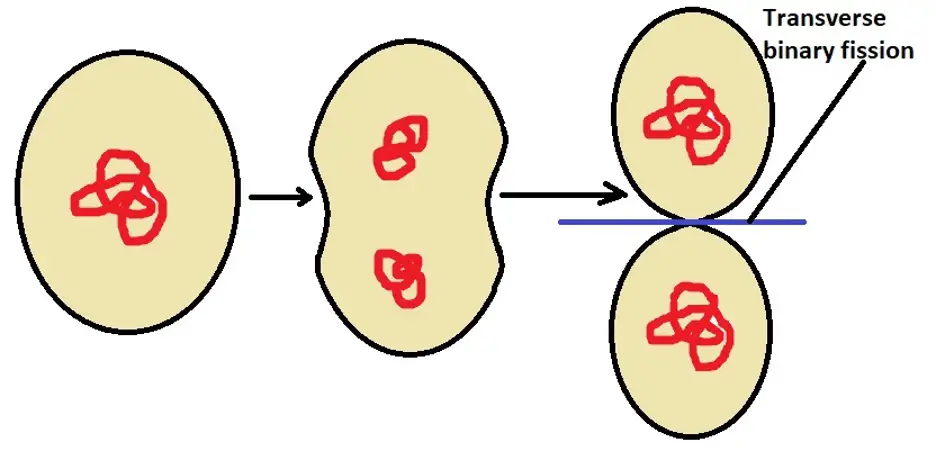

As is the case with Paramecium, cell division in Rickettsia bacteria occurs through a process known as transverse binary fission. This is a type of asexual reproduction where the parent cell divides to produce two similar daughter cells. Here, cell division (fission) takes place along the transverse plane.

Generally, cell division starts with division of the DNA through replication. This is a process through which the DNA is copied in order to produce two identical molecules of DNA.

Following replication, the two molecules of DNA are separated (karyokinesis) which is followed by division of the cytoplasm , characterized by the formation of a furrow in the plasma membrane. Eventually, the furrow deepens resulting in division of the cytoplasm (cytokinesis) before the two cells completely separate.

The following is a general representation of transverse binary fission in Rickettsia bacteria:

* In the absence of sufficient nutrients, rickettsia bacteria may start growing into long filaments. However, these filaments undergo rapid division when nutrients are provided to produce single cells that are rod-shaped

Disease

Rickettsia bacteria are responsible for a number of diseases/infections which are collectively known as rickettsiosis.

Depending on the disease/infection, these bacteria are transmitted to the host by given vectors which may include mites, ticks, lice, or fleas. As mentioned, these bacteria are generally divided into two main groups depending on the type of disease/infection they cause.

This section will focus on the two types of infection and how they are transmitted:

Typhus group rickettsiosis

Also known as typhus fevers, typhus includes infections that are caused by several Rickettsia bacteria. A week or two after the initial infection, an individual may experience a number of symptoms that include chills, headache, fever, and muscle aches among others.

With regards to severity, there are two types of typhus which include:

Endemic typhus: Also known as murine typhus, endemic typhus (Endemic typhus fever) is an acute form of typhus fever that is primarily caused by R. typhi. However, studies have shown that it can also be caused by R. felis.

The natural reservoir of R. typhi is rats. For this reason, the infection is sometimes associated with poor hygiene.

When fleas, Xenopsilla cheopsis, acquire the bacterium from infected rats, it may be transmitted to a human host through several ways that include:

· Flea bite followed by the introduction of infected feces (of the flea) into the bite wound

· Scratching a given area of the skin resulting in self-inoculation when an individual comes in touch with infected flea feces

· Introduction of infected flea feces into a wounded site in the skin

· Entry through the respiratory system

· Entry through the eye (the conjunctiva)

Following entry into the body, the bacterium is transported to the target site (endothelial cells) through the lymphatic system or the blood.

Using the OmpB proteins located on the surface outer membrane, the bacteria are also able to adhere to the endothelial cells. This allows the bacterium to interact with given a protein (Ku70) on the surface of the cell (host cell) which results in the internalization of the pathogen through a process known as phagocytosis.

In the cell, the bacterium then escapes into the cytoplasm before the vesicle fuses with the lysosome. This allows it to avoid being destroyed. In the cytoplasm, the bacterium can continue growing and reproducing and spread to the neighboring cells as the cycle continues.

Because of the free radicals produced, the host cells are directly affected.

* Symptoms like fever, headache, rashes, and musculoskeletal pain start manifesting a week or two following the initial infection.

Treatment: In many countries, the incidence of endemic typhus has been significantly reduced by improving hygiene (reducing rat and rat flea population).

While no vaccine is available, doxycycline is the primary treatment option for this disease.

Epidemic typhus: Also known as louse-borne typhus, epidemic typhus is a type of typhus fever that is caused by Rickettsia prowazekii. Unlike endemic typhus which is mostly transmitted by rat fleas, epidemic typhus is generally transmitted by a body louse known as Pediculus Humanus Corporis.

The natural/main host of R. prowazekii is the human body. Therefore, the body louse acquires the bacterium when it feeds on the blood of an infected patient.

In the alimentary tract of the body louse, the bacterium can continue reproducing before they are transmitted to the human host when the body louse feeds again. For the most part, the bacterium is transmitted when the louse bites a given part of the body causing an individual to scratch the wound.

This results in the contamination of the wound with feces of the louse which contains the bacterium. This is especially common in cases where individuals share clothes with infected lice or in places where people crowd together in cold seasons.

* As it grows and proliferates in the alimentary tract of the vector (body louse) R. prowazekii has been shown to cause an obstruction which results in the death of the vector within one (1) or three (3) weeks.

For this reason, the bacterium is not usually passed down from the parent to the offspring.

* Rickettsia prowazekii can survive in the feces of the vector (body louse) for about 100 days. For this reason, an infection may also occur in cases where it is blown by wind with, along with dust.

Here, an infection occurs through the respiratory system. Moreover, it can persist in the human for many years even after treatment.

Once this bacterium enters into the cells of the host (cells of the vascular endothelium) it causes vasculitis and infiltration of the vascular endothelium tissue by leukocytes.

About two (2) weeks after the initial infection, some of the main symptoms of epidemic typhus may include chills and fever, rashes, a headache, muscle aches, nausea, and vomiting, etc.

Treatment: Given that epidemic typhus is transmitted by body lice, preventive measures involve avoiding areas that are overcrowded and improving hygiene (regular bathing, properly cleaning cloths and beddings, avoiding sharing clothes, treating infested clothing/beddings with 0.5 percent permethrin).

For individuals who are already infected, however, treatment with doxycycline is effective and leads to a quick recovery.

Spotted fever group rickettsioses

Spotted fever group rickettsioses are diseases caused by several Rickettsia bacteria.

There are several types of spotted fever group rickettsial diseases that include:

Rocky Mountain spotted fever: Rocky Mountain spotted fever is common in North and South America. It's caused by the bacterium Rickettsia rickettsii which is often transmitted by ticks. During its life cycle, the bacterium is first acquired from infected rodents like chipmunks and mice, etc. (reservoirs) when the tick is feeding.

During mating, male ticks can also transmit this bacterium to the female tick through the spermatozoa or other body fluids. The bacterium can then be transmitted to a human host (or dog) when the vector is feeding.

In the body, the bacterium invades and multiples in the cells of the vascular endothelium as well as the cells of the smooth muscles. Here, they can cause vasculitis and thrombosis.

Some of the symptoms of this infection may include petechial or purpuric maculopapular rashes, necrosis, abdominal pain, as well as myalgia (muscular pain), etc.

Treatment: For patients with rocky mountain spotted fever, treatment using Doxycycline has proved effective for both adults and children. However, for patients who may be allergic to this drug, Chloramphenicol is often used.

Boutonneuse fever: Boutonneuse fever is also known by several other names depending on the region. For instance, in Kenya, it's known as Kenya tick typhus which in India is referred to as Indian tick typhus.

This type of spotted fever disease is caused by the bacterium Rickettsia conorii which is transmitted by the dog tick, Rhipicephalus sanguineus.

During the life cycle of the bacterium, it's acquired from infected dogs and some rodents by the tick and transmitted to the human host through a bite or when infected feces of the tick enter a wound.

By using the surface protein, rOmpB, the bacterium is able to bind to the protein Ku70 located on the surface of the host cell which in turn results in a series of events that allows the bacterium to enter the cell.

Like some of the other Rickettsia bacteria, the bacteria invade endothelial cells as well as hepatocytes where it may cause tissue necrosis. Some of the symptoms (about 5 days after the infection) may include chills, fever, malaise, myalgia, and headache, etc.

Treatment: While Doxycycline is the drug of choice for patients with Boutonneuse fever, other tetracyclines like Chloramphenicol and Quinolones are also used for treatment purposes.

Flea-borne spotted fever: Also known as California pseudotyphus, flea-borne spotted fever is caused by the bacterium Rickettsia felis which is transmitted by fleas. As the name suggests, the bacterium is found in cats. When the fleas acquire the bacteria from infected cats, they can transmit it to the human host during feeding.

Unlike some of the other diseases, this bacterium is mostly transmitted through the saliva of the flea while they are feeding rather than the feces. In the vectors, the bacterium has been identified in several regions including the epithelial lining of the midgut, the ovaries, as well as the muscles, etc.

Like Rickettsia typhi, Rickettsia felis also uses the protein OmpB to adhere and enter the cells. This infection is characterized by such symptoms as maculopapular rash, fever, headache, and myalgia, etc.

* This type of disease can also be transmitted to dogs and other rodents.

Treatment: As is the case with the other rickettsial diseases, Doxycycline is the drug of choice for flea-borne spotted fever.

Some of the other types of spotted fever group diseases include:

· African tick typhus: Common in parts of Africa and West Indies and is caused by the bacterium, Rickettsia africae. It's normally found in cattle: Some of the treatment options for African tick typhus include Azithromycin, Doxycycline, and Chloramphenicol

· Rickettsial pox: Caused by Rickettsia akari and is normally transmitted by house mite. Treatment may involve the use of Doxycycline or Chloramphenicol

Bacteriology as a field of study

Bacterial Transformation, Conjugation

How do Bacteria cause Disease?

Bacteria - Size, Shape and Arrangement - Eubacteria

List of Diseases caused by Bacteria

Return to Parasitology main page

Return from Rickettsia Bacteria to MicroscopeMaster home

References

M. Alejandra Perotti, Heather K Clarke, Bryan D Turner, and Henk Braig. (2006). Rickettsia as obligate and mycetomic bacteria.

Matthew T. Robinson et al. (2019). Diagnosis of spotted fever group Rickettsia infections: the Asian perspective

R. Premaratna. (2016). Epidemiology and ecology of rickettsial infections.

William A. Petri. (2020). Overview of Rickettsial Infections.

Xue-jie Yu and David H. Walker. (2012). Rickettsia and Rickettsial Diseases.

Links

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/279762438_Murine_Typhus

https://www.britannica.com/science/rickettsia-microorganism-group

Find out how to advertise on MicroscopeMaster!