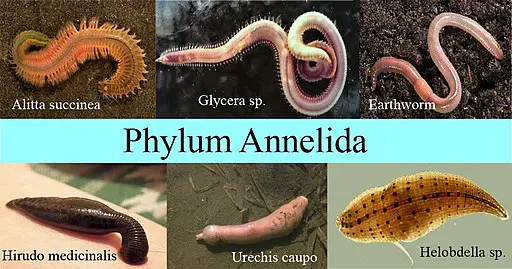

Phylum Annelida

Examples and Characteristics

Annelids (members of the phylum Annelida) are triploblastic bilaterally symmetrical animals with a segmented body (they are also known as segmented worms). With an estimated 22,000 species, the phylum is morphologically diverse and comprises of four main classes.

These include:

· Polychaeta (also known as polychaetes and include bristle worms)

· Oligochaeta (Earthworms)

· Hirudinea (Leeches)

· Archiannelida (E.g. Polygordius)

Characteristics

Phylum Annelida Anatomy/Morphology

All annelids are bilaterally symmetrical triploblastic organisms with a segmented body. However, there are various differences between members of the four classes.

The following are anatomical/morphological characteristics of the four main groups of Phylum Annelida:

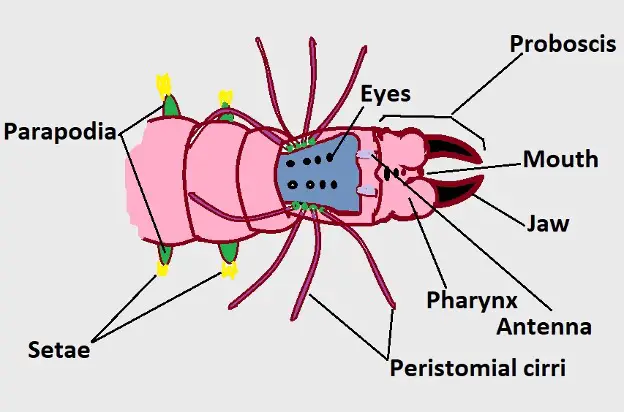

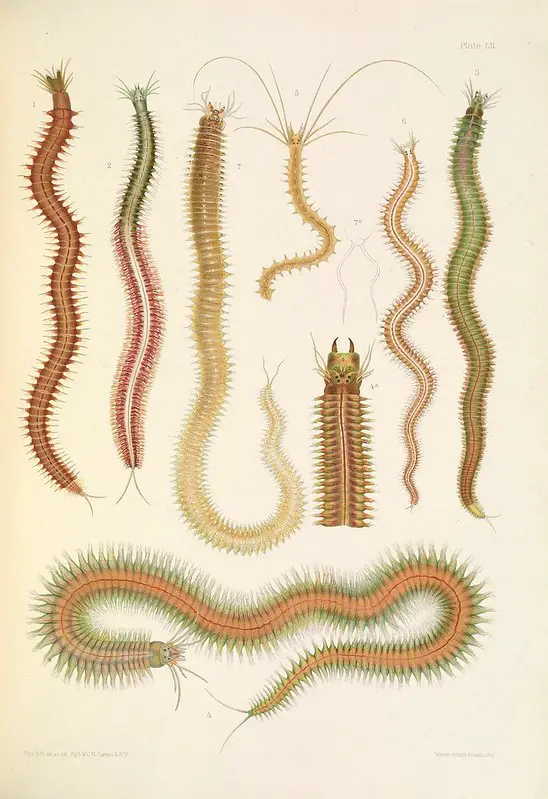

Polychaeta (The name polychaete comes from the Greek words "poly" meaning many and "chaeta" which means bristle)

The class Polychaeta comprises bristle worms and is the largest group within the phylum Annelida (with over 10,000 species). Like the other annelids, bristle worms are bilaterally symmetrical organisms with a segmented body. The head region consists of the prostomium (acron), a peristomium, and a pharynx. The prostomium is located above the mouth and acts as a mouth covering.

In some species, the prostomium has been shown to be retractile. Depending on the species, some of the features that can be identified on the prostomium include the eyes, tentacles, palps (act as sensory or feeding appendages depending on the animal), and antennae (sensory organs).

The peristomium is located next to the prostomium and is generally considered to be the first true body segment in polychaetes. It consists of the mouth, testicular cirrus, and a proboscis.

When viewed under the microscope, it's possible to observe chaetae and chitinous jaws on the proboscis. The pharynx, which is the third part of the head region, makes up the anterior part of the digestive tract. While it's mostly used for feeding, it's reversible (it can be turned outwards) and can be used for burrowing in some species.

The rest of the body (trunk) is segmented with a number of important internal and external features/organs. For instance, in each of the other segments, polychaetes have ganglion (cluster of nerves) and tubule openings (nephridium) used for excretion.

On each side of the segments, many of the species also have parapodia (unjointed extension from the body wall) used for locomotion (especially for crawling and swimming), sensation, and respiration.

While they display some variation in structure between different species, these structures consist of a dorsal notopodium and a ventral neuropodium. For burrowing polychaetes (e.g. Capitella species), the parapodia may be slightly raised with hooked chaetae (uncini). For these species, the parapodia may serve a number of important functions including feeding and forming tubes in addition to locomotion.

Here, the chaetae also varies significantly from compound to pectinate, etc. Lastly, the tail end of the organism may be truncated and consists of a dorsal or terminal anus and cirri.

* Polychaetes are also known as bristle worms because each of the segments are characterized by parapodia which have bristles (chaetae). Some examples of polychaetes include bloodworms, sea mice, ragworms, and lugworms/sandworms.

* Members of this group also vary in size from a few millimeters to about 3 meters in length.

* Tube-dwelling species are classified in the subclass Sedentaria while actively moving members belong to the subclass Errantia.

Oligochaeta

Oligochaetes are perhaps some of the most common annelids. Like all the other annelids, they have an elongated, bilaterally symmetrical, segmented body. Compared to Polychaeta and Hirudinea, the class Oligochaeta has been shown to be more diverse and abundant (with over 3,000 species) and can be found in different types of habitats.

Unlike Polychaetes, Oligochaetes do not have a clearly defined head. For this reason, it may prove challenging for some people to distinguish between the head end and tail end of these animals. Here, then, one of the best ways of locating the head region is finding the end that is closest to the clitellum.

The anterior part of these organisms, where the head should be located, consists of the prostomium which covers the mouth. The mouth is located on the second segment. Some of the other organs/features that can be found in the anterior region include the buccal cavity, the brain (also known as the cerebral ganglia), pharynx, and the circumpharyngeal connective.

The rest of the body is segmented with between 100 and 150 segments in earthworms. Each of the segments has four or more pairs of chitinous setae (bristle). The setae extend from the body cuticle and are moved by tiny muscles.

Here, however, it's worth noting that for the most part, locomotion among these animals is made possible by peristaltic movements (contraction and relaxation of the muscles). The body is covered by a cuticle with circular and longitudinal muscle beneath. Some of the other organs contained within the body cavity include the nephridium, intestinal lumen, setal retractor muscle, and the tryphlole, etc.

* The setae serves to anchor the body thus preventing it from slipping etc.

* The clitellum, a thick ring-like structure on the epidermis, is a mucus secretory section involved in sexual reproduction.

* Some examples of species in the group Oligochaeta include pot worms, ice worms, and blackworms, etc.

Hirudinea (true leeches)

Also known as true leeches, members of the class Hirudinea are bilaterally symmetrical animals with 33 to 34 segments. Like most of the other annelids, leeches are soft-bodied organisms with a cylindrical body (ranging from about 10mm to 34mm in length).

The head region contains 4 to 5 pairs of eyes, jaws, a pharynx, jaws, and a ridge of teeth (located on the anterior sucker). Some of the leeches possess a proboscis used for engulfing prey. In addition to its role in feeding, the anterior sucker (together with the posterior sucker) plays an important role in locomotion.

The rest of the body, as mentioned, consists of 33 to 34 segments. Unlike some of the other annelids, they lack chaetae and septa and have highly reduced parapodia. However, like earthworms, they have a clitellum which is used during sexual reproduction.

* There are over 700 members of Hirudinea. Some examples of these species include Calliobdella lophii, Hemibdella soleae, Ostreobdella species and Theromyzon species.

Archiannelida

Archiannelida is a small group that consists of simple annelids. Like the other annelids, members of this group have an elongated body. However, segmentation among these species is faint and they lack setae and parapodia.

* Many of the species that were once classified under the class Archiannelida have either been retracted from the group or remain in contention.

Habitat/Distribution

Phylum Annelida are commonly found in aquatic environments (marine and freshwater habitats) and terrestrial habitats like damp soil throughout the world.

* The majority of phylum Annelida (81 percent) are found in marine environments. 12 percent of all annelids are found in freshwater while 7 percent are found in terrestrial habitats.

Marine Annelids

Members of the class Polychaeta (bristle worms and fan worms) are commonly found in marine and estuarine waters. In the marine environment, they can be found in several habitats including deep hydrothermal vents and coral reefs.

The leg-like structures known as parapodia can be used for various functions depending on the habitats in which the animal resides in this environment. For instance, while they can be used for swimming (by free swimmers), they are also used for walking around the seafloor or burrowing in the mud at the shore.

* Bristles found on parapodia protect these annelids (Polychaetes) from some predators. They not only make it rather challenging for the prey to swallow but also produce venom in some species.

* In water, parapodia is also used to circulate direct oxygenated water into tight spaces.

* They have gills for respiration.

* Members of the class Archiannelida are also marine animals.

Terrestrial Annelids

Also known as angleworms, earthworms, members of the class Oligochaeta, are some of the most popular terrestrial annelids. Although they can be found in drier areas, they are commonly found in moist habitats with plenty of organic content.

While they lack eyes, earthworms use the prostomium among other sensory structures to guide them through the soil. The muscular mouth makes it easier to eat the soil as they burrow. The soil is then excreted with the help of mucus.

As they make their way into the tunnels or move on various surfaces, the setae on each body segment has been shown to help anchor the animal or at least control movement. However, locomotion on surfaces is made possible by the contraction and relaxation of the longitudinal and circular muscles.

* Given that gaseous exchange occurs through the skin in earthworms, they are commonly found in moist soils (or aquatic environments) to protect their bodies from dying. Here, mucous and body fluids of the organism also keeps the skin moist.

Freshwater Annelids

Like some earthworms, the majority of leeches, in the class Hirudinea, can be found in freshwater habitats and in some terrestrial habitats.

They have a number of important adaptations that have allowed them to survive in freshwater environments. Although they have poor vision (their eyes only allow them to differentiate between dark and light), this allows them to determine their location in water (e.g. whether they are near the surface or deeper in water) or detect predators.

In addition to the five pairs of simple eyes, they also have chemoreceptors on their head through which they can detect various chemicals in their surroundings and therefore move in the direction of prey. Typically, swimming is made possible by a wave-like motion while movement at the bottom of lakes or ponds, etc. is achieved through looping.

Here, the anterior sucker is first used to attach the organism to a surface. Contraction of the muscles pulls the posterior part of the body forward and the posterior sucker again attaches to the surface. A repeat of this process allows the animal to move on various surfaces both in aquatic habitats and on land.

Phylum Annelida Reproduction/Lifecycle

While some annelids are capable of both sexual and asexual reproduction, others are only capable of one mode of reproduction.

Reproduction in Polychaetes and Oligochaetes

Sexual and asexual reproduction - Polychaetes and Oligochaetes can reproduce sexually and asexually. Unlike sexual reproduction, asexual reproduction does not involve an exchange of gametes. Rather, it occurs through budding or fission.

Essentially, budding involves the development of a new individual from an adult form. Here, the adult individual develops a bud which develops over time into a new individual with similar characteristics to the parent.

When fully developed, the new individual breaks off from the parent and is capable of reproducing through the same process. Fission, on the other hand, is the process of asexual reproduction where the parent organism splits into two with each part regenerating the missing part to form a complete organism. This type of reproduction is common in worms with high regenerative capabilities (e.g. Syllidae species).

Sexual reproduction involves the fusion of gametes to form a new individual. Here, however, it's worth noting that the majority of Polychaetes are dioecious organisms (separate male and female individuals). Oligochaetes are hermaphrodites with each member having a male and female reproductive organ.

In Polychaetes, studies have shown them to undergo a physical transformation during sexual reproduction. The transformation converts given posterior structures into reproductive organs that can produce gametes.

Usually, they will swim to the ocean surface where they release gametes (fertilization occurs externally). The zygote then transforms into a larva (trochophore larva) that develops and matures into an adult over time.

Unlike Polychaetes, Oligochaetes are hermaphrodites and sexual reproduction involves mating. During mating, the sperm cells are deposited and stored in the spermatheca (a sac-like structure).

The eggs and sperm are then deposited in a cocoon (the cocoon is secreted by the clitellum) where fertilization takes place. The embryo then emerges from the cocoon and develops into an adult without going through the larval phase (direct development).

Sexual reproduction in Hirudinea - Unlike Oligochaetes and Polychaetes, members of the class Hirudinea are only capable of sexual reproduction. However, like Oligochaetes, they are hermaphrodites and therefore possess both male and female reproductive organs.

Here, reproduction also involves mating with the clitellum producing mucus that keeps the two members paired. Like some of the other annelids, sperm cells are stored in the spermatheca to be used for fertilization. Here, however, the eggs are fertilized internally and are only released into the cocoon after fertilization has taken place. The embryo skips the larval stage and directly develops into an adult form.

Circulatory System and Respiration

Phylum Annelida have a closed circulatory system which means that blood is contained in blood vessels at all times. Generally, the circulatory system consists of two main vessels (the ventral and ventral dorsal blood vessels). Whereas the ventral vessel transports blood from the head region of the organism to the tail, the dorsal vessel carries blood in the opposite direction (from the tail to the head).

In addition to the two vessels, there are two smaller blood vessels within each body segment that connects the two main vessels as well as numerous small capillaries that pervade the skin/epidermis. These capillaries are important for respiration given that gaseous exchange occurs through the skin.

In aquatic environments or terrestrial habitats, oxygen diffuses through the skin and enters the capillaries to be transported by blood while carbon dioxide diffuses out.

* In some species, specialized gills are used for respiration.

* Blood is either pumped around the body by actions of the muscular dorsal blood vessel or heart-like vessels at the anterior part of the body.

Nervous System

According to studies, Phylum Annelida display significant variation in their nervous system organization. In most species, however, the nervous system consists of a simple brain, a ganglion, and nerve fibers.

In earthworms, the brain is a bilobed mass known as cerebral ganglia. It's connected to the ventral nerve cord which runs through all the body segments. Within each segment. the ventral nerve runs into a ganglion which consists of nerve tissue. Nerve fibers also extend from the ganglion and extend into parts of the segment.

* Annelids have a number of sensory organs including the eyes, antennae, and palps.

Feeding and the Digestive System

Annelids can be found in different habitats and therefore have access to different food sources. Oligochaetes (earthworms) are deposit feeders and therefore obtain nutrients by ingesting soil as they burrow through the soil.

Because of their ability to break down debris (leaves, grass, etc.), they are often used in agriculture to improve the quality of the soil.

Unlike earthworms, annelids found on the seafloor (Polychaetes) survive by feeding on other organisms as predators, feeding on dead organisms as scavengers, or by eating suspended material as filter feeders. Lastly, some of the annelids rely on other organisms (hosts) for nutrition. As such, they exist as parasites (e.g. leeches).

Despite having different food sources and some differences in their digestive system, all annelids have a complete digestive tract that consists of a mouth, a pharynx, esophagus, stomach, intestine, and anus. Food material pass through these parts before waste materials are excreted through the anus.

Some unique features found in different annelids and their functions include:

A proboscis with jaws and teeth - These features are common in leeches. They are used for cutting the skin in order to suck blood from the host.

Gizzard - In earthworms, the gizzard serves to break down soil in order to extract organic matter (the nutrients they need for survival).

Anti-clotting and analgesic agents - Because they survive by feeding on the blood of the host, studies have shown leeches to produce anti-clotting and analgesic agents in their saliva that prevents the host from feeling pain or losing bleeding excessively. This promotes their parasitic lifestyle.

What does Phylum mean in Biology?

Return to Worm under a Microscope

Return from Phylum Annelida to MicroscopeMaster home

References

C.S. Andrade et al. (2015). Articulating “Archiannelids”: Phylogenomics and Annelid Relationships, with Emphasis on Meiofaunal Taxa Sónia.

Greg Rouse and Fredrik Pleijel. (2006). Reproductive Biology and Phylogeny of Annelida.

P.S.Verma. (2001). Invertebrate Zoology (Multicolour Edition).

R. P. Kostyuchenko, V. V. Kozin, and E. E. Kupriashova. (2015). Regeneration and Asexual Reproduction in Annelids:Cells, Genes, and Evolution.

Links

https://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/14-fun-facts-about-marine-bristle-worms-180955773/

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/281031251_Annelida

Find out how to advertise on MicroscopeMaster!