Antique Leeuwenhoek Microscope

The Lens - Observation of Specimens

The Leeuwenhoek microscope was a simple single lens device but it had greater clarity and magnification than compound microscopes of its time.

Designed around 1668 by a Dutchman, Antony van Leeuwenhoek, the microscope was completely handmade including the screws and rivets.

An unlikely scientific pioneer, van Leeuwenhoek didn’t begin experimenting with microscopes until he was past the age of 40.

About Antony Van Leeuwenhoek

The son of a basket weaver, van Leeuwenhoek was not privileged as were most scientists of the period. His education was basic, but he was driven by curiosity and had a gift for recording his observations.

As a fabric merchant by trade, his first experience with microscopy was examining threads and cloth under a magnifying glass. He gained skill in making his own lenses and then building the microscope frame to hold them.

Some people refer to him as the father of the microscope, although compound microscopes had been in existence for 50 years prior to van Leeuwenhoek’s birth.

Due to his discovery and classification of microorganisms, he could rightly be called the father of microbiology. His research garnered him membership in the Royal Society of London in 1680.

The Van Leeuwenhoek Microscope

The method for making the van Leeuwenhoek microscope generated much interest.

He loved to demonstrate his microscopes and, while his lens crafting techniques were not unique, the precision with which he made his lenses was incredibly keen for the day.

With over 500 different microscopes to his credit, van Leeuwenhoek seemingly made a microscope for every specimen he examined. Fewer than 10 are still intact and in museums but many more of his lenses survive to this day.

The frames for the van Leeuwenhoek microscope were made of copper, bronze, or occasionally silver. The frame was actually two plates that held the single lens between them in line with a small hole. A static specimen was mounted on a pin that was mounted on a block in the field of view of the lens. Two screws adjusted the distance between the specimen and the lens and also the height of the specimen in the field of view.

For examining liquids a small glass tube was clamped behind the lens in its field of view. Less than four inches in length, practice was required to use the microscope properly.

The microscope had to be held as close to the unblinking eye as possible and the small lenses had a high degree of curvature which made for a short focal length. With his strongest lenses the specimen had to be within 4/100th of an inch from the lens.

The usual viewing method for the van Leeuwenhoek microscope involved resting it on the viewer’s cheek or forehead and turning the focusing screws until the specimen could be seen in clear detail. Then, by turning the body and changing the angle of the microscope proper light was focused onto the specimen.

Differing designs of the van Leeuwenhoek microscope were similar in size and viewing methodology, but some had up to three lenses mounted side-by-side and were slightly wider to accommodate the lenses.

The Lens

The lens of the van Leeuwenhoek microscope gave it an advantage over the compound microscopes of that time period.

Those microscopes had problems with distortion and aberration which resulted in a usable magnification of 30X or 40X. The Ultrecht Museum in the Netherlands has a van Leeuwenhoek microscope in its collection with a magnification of 275X.

He devoted an inordinate amount of time to perfecting his lens crafting and used the three basic methods of grinding, blowing, and drawing.

In grinding the lens, van Leeuwenhoek would polish the lens with compounds of increasingly fine grit until no imperfections on the glass remained. Of the surviving van Leeuwenhoek lenses, all but one of them was manufactured by this process. In the blown glass method, he would use the small piece of glass at the end of a blown glass tube and then polish it.

In the drawing method, van Leeuwenhoek would place the middle of a glass rod in a flame and gradually pull it apart as it melted. This resulted in two separate glass rods tapering to fine points. He then inserted the tiny point of one of the rods into the fire and that created a small glass sphere on its end. This small sphere was used as a lens.

Gravity would cause the glass to be asymmetrical but by twirling it on the end of glass rod van Leeuwenhoek could make an almost perfectly spherical lens. The smallest of van Leeuwenhoek’s surviving glass spherical lenses is only 1.5 mm in diameter.

Visibility of the Specimen

The van Leeuwenhoek microscope and lens solved the problems of magnification and resolution, but to be useful the specimen had to be visible in the field of view. Some of his specimens were transparent and some were opaque.

- For opaque specimens, such as minerals or rocks, he used reflected light or the dark field method of illumination. By shining a light on the specimen from the side and pointing the microscope towards a dark background the surface details became visible. One reason he made microscopes from silver was in the hope that the metal would better reflect light onto the surface of an opaque specimen.

However, this was not efficacious and didn’t warrant the expense. - Transparent objects needed to be viewed with light transmitted through the specimen. In certain types of specimens some light is transmitted but enough is absorbed to provide contrast to view the details of the object.

However, when viewing completely transparent objects through the van Leeuwenhoek microscope, he learned to stain the specimen with saffron to make the details visible.

His Observations

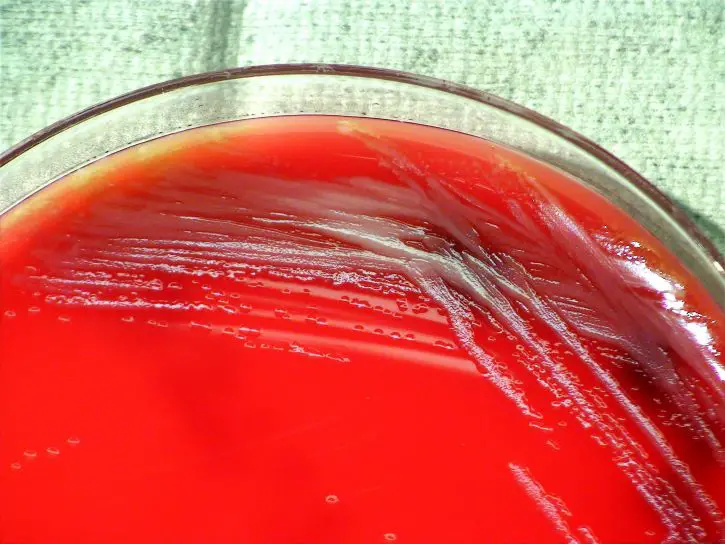

The van Leeuwenhoek microscope provided man with the first glimpse of bacteria.

In 1674, van Leeuwenhoek first described seeing red blood cells. Crystals, spermatozoa, fish ova, salt, leaf veins, and muscle cell were seen and detailed by him. Although he wasn’t a skilled artist, he employed one to depict what he described.

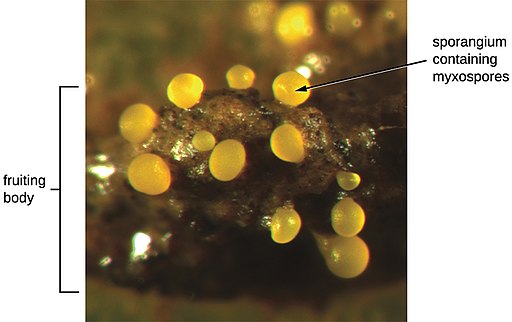

Nematodes, rotifers, and planaria he named animalcules. Van Leeuwenhoek recognized that they were living organisms but knew not what to call them since nobody had seen them before.

Using his microscope, he was the first person to discover blood circulation in the capillaries. He used a microscope to show this circulation in the tail of an eel to Tsar Peter the Great of Russia in 1698.

Legacy

Predominately because it was so difficult to learn to use, the van Leeuwenhoek microscope was never used by other scientists in their research.

However, its magnification and resolution were so advanced that it would be the middle of the 19th century before the compound microscope could open the door to the world of microbiology as van Leeuwenhoek’s had done.

Each microscope was handmade and one-of-a-kind, and in designing them van Leeuwenhoek had to overcome the problems of magnification, resolution, and visibility using his own ingenuity.

Return from Leeuwenhoek Microscope to Antique Microscope

Return to Best Microscopes Home

Find out how to advertise on MicroscopeMaster!